COP Climate Deal 2021

Coal Stacks Burning Against the Sunset

For more than a century, scientists have understood the basic physics behind why greenhouse gases like carbon dioxide cause warming. These gases makeup just a small fraction of the atmosphere but exert outsized control on Earth’s climate by trapping some of the planet’s heat before it escapes into space. The greenhouse effect is important: It’s why a planet so far from the sun has liquid water and life. However, during the Industrial Revolution, people started burning coal and other fossil fuels to power factories, smelters, and steam engines, which added more greenhouse gases to the atmosphere. Ever since human activities have been heating the planet.

COP stands for “conference of the parties”, and is a summit where the 197 signatories to the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC) – 196 countries and the EU – come together to make decisions on how to implement the treaty initially made in at the Rio Earth Summit in 1992. This is the first COP since COP25, held in Madrid in 2019. The 26th UNFCCC conference, COP26 was originally due to take place in November 2020 but was postponed because of the coronavirus pandemic. COP26 is the first major test of the 2015 Paris Agreement.

Why does this matter to us? In just the past few decades: Rising temperatures have worsened extreme weather events. Chunks of ice in the Antarctic have broken apart. Wildfire seasons are months longer. Coral reefs have been bleached of their colors. Mosquitoes are expanding their territory, able to spread disease. The only thing to blame is ourselves.

Earth has already warmed by about 1 degree Celsius, or 1.8 degrees Fahrenheit, since the 19th century, before industry started to boom. While we experience the effects, we’re on our way toward 1.5 degrees C (2.7 F) by as early as 2030. One way to look at the 1.5°C challenge is in temperature terms. The global average in 2020 was 1.1-1.3°C warmer than pre-industrial levels, and that figure is rising by 0.1-0.3°C each decade. The pledges made at the time of the Paris agreement in 2015 led climate modelers to project a “best guess” of 2.7°C of warming by 2100. The more ambitious ones made in Glasgow reduced that by perhaps 0.3°C.

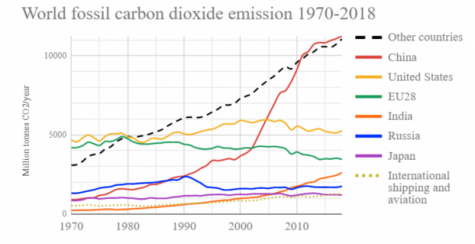

The draft text, the final version of which will summarise the decisions made in Glasgow, currently calls upon parties to “[accelerate] the phaseout of unabated coal power and of inefficient subsidies for fossil fuels”, the first time that fossil fuels have been mentioned in a United Nations text about climate change since the Kyoto Protocol in 1997. The jury is out on whether the clause will remain in the final text. Fossil-fuel producers are keen to see it excised. Yet there was strong support for it in this afternoon’s plenary. Almost all countries asked for the clause to remain and many wished for it to be strengthened by calling for the removal of all fossil fuel subsidies, not just “inefficient” ones. China (the largest emitter), Russia, and Saudi Arabia were noticeably silent on the matter.

Ava Braiter (11) states, “Fossil fuels, specifically coal, are a huge contributor to climate change.” “I believe that this agreement can be a key factor in slowing down climate change since coal is the most harmful fossil fuel. Coal releases many toxic substances that contribute to climate change such as CO2, sulfur, mercury, lead, and particulate matter.” She strongly believes that countries like China, the US, and India need to work faster and harder to lessen their emissions. She states, “People in populated cities like Beijing are experiencing respiratory issues caused by the burning of fossil fuels and driving cars.”

Mr. Clarkson, an Environmental Science teacher at Wheeler, stated, “Something immediately needs to be done. We are already on a crash course to a lot of environmental disasters, and if we continue on our current pace, it will be worse.” As an individual, he does little things like “reducing meat consumption, looking into electric cars, and recycling.”

Mr. Dezern, the horticulture teacher at Wheeler, states, “The carbon in the ground, needs to stay in the ground. Any carbon removed needs to have efforts to restore the carbon like reforestation.”

He does admit that as an individual, it is tough to find ways to help on such a small scale, as most- if not all- greenhouse gases are admitted on a large scale. But, like Mr. Clarkson, he and his wife have reduced their meat consumption to once a week. He acknowledges change needs to come from legislation, but he says you have to strike a balance by helping out on a smaller scale and to support those large-scale changes.

Maddie is a senior, and this is her second year in journalism. This year, she is taking on the role of News Editor and Edit in Chief. She has been on the...